An important component for a successful MEB (Multi-Evidence-Base) process is that it addresses a real concrete issue that concerns or interests all actors involved. What the issue is and how to understand and formulate the different perspectives that surround it, needs to be discussed and agreed upon in collaboration from the onset. The perceptions of what the problem is may vary significantly from different points of view. This needs to be taken into account in formulating the issue to be enriched, so that it can capture the experiences and perspectives of knowledge holders representing different, and equally valid, knowledge systems.

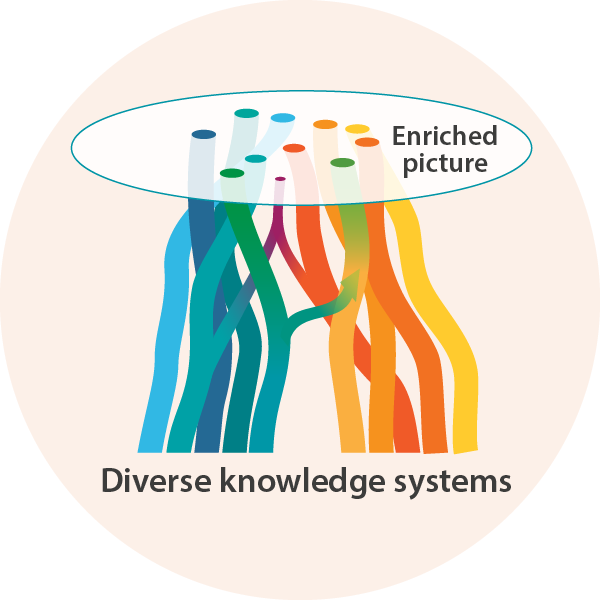

The MEB approach views different knowledge systems as making complementary contributions and emphasises that joint analysis among actors assists in working both with convergence and divergence. For example, Molnár et al. (2016) highlights that when discussing approaches to conservation in the Hungarian steppe, local herders have their livelihood at the core of their knowledge, such as how they can manage the behaviour of their grazing animals to promote the health and diversity of grass assemblages for production. In comparison, conservationists working in the same landscapes focus almost solely on the protection of the plants themselves, with little regard to the impact on grazing animals. If this difference is ignored or framed as a problem, it has the potential to create tension when attempting to collaboratively design and implement conservation initiatives in the region. Conversely, these different perspectives can be worked together to provide an enriched picture of exactly what is necessary for maintaining and enhancing biodiversity and social–ecological system function in the steppe.

Another example is the “Two-Eyed Seeing” (Etuaptmumk in Mi’kmaw) which embraces the idea of “learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of mainstream knowledge and ways of knowing, and to use both these eyes together, for the benefit of all”. Reid et al. (2021) apply Two-Eyed Seeing in three Canadian aquatic and fisheries case-studies for co-developing questions, documenting and mobilising knowledge and co-producing insights and decisions in research and management contexts.

International exchange meeting for mobilisation of indigenous and local knowledge for community and ecosystem wellbeing

International exchange meeting for mobilisation of indigenous and local knowledge for community and ecosystem wellbeing